By Antonio Gramsci, May 4, 1918

|

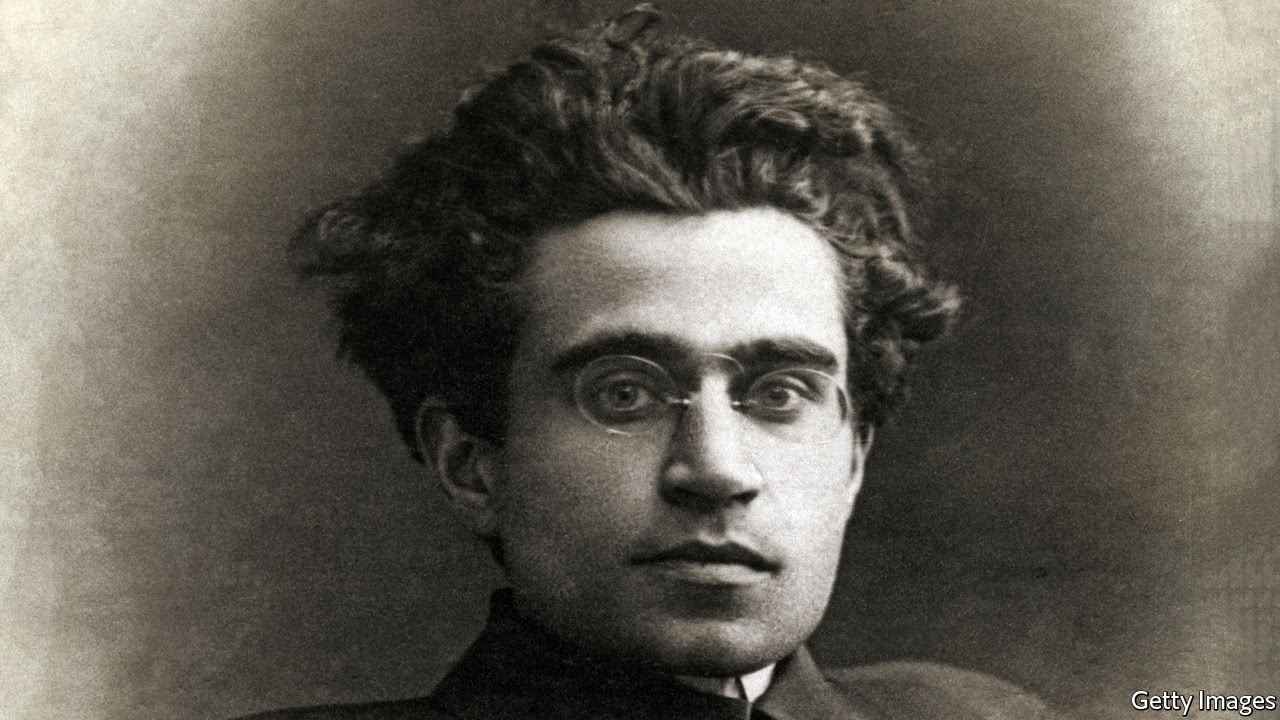

| Antonio Gramsci, 1891-1937 |

Are we Marxists? Do Marxists exist? Stupidity, thou alone art immortal. The question will probably be taken up again over the next few days, the period around Marx's centenary, and will bring forth rivers of ink and idiocy. Wild mumblings and stylistic affectation are the incorruptible heritage of man. Marx did not write a nice little doctrine, he is not a Messiah who left a string of parables laden with categorical imperatives, with absolute, unquestionable norms beyond the categories of time and space. The only categorical imperative, the only norm: 'Workers of the world, unite!' The duty of organizing, the propagation of the duty to organize and associate, should, therefore, be what distinguishes Marxists from non-Marxists. Too little and too much: who in this case would not be a Marxist?

And yet that is how it is. Everyone is a bit of a Marxist, without being aware of it. Marx was great, his action was fecund, not because he invented from nothing, not because he extracted an original vision of history from his imagination, but because in him the fragmentary, the incomplete, the immature became maturity, system, awareness. His personal awareness can become everyone's, it has already become that of many people: because of this Marx is not just a scholar, he is a man of action; he is great and fecund in action as in thought, his books have transformed the world, just as they have transformed thought.

Marx signifies the entry of intelligence into the history of humanity, the reign of awareness.

His work falls in exactly the same period as the great battle between Thomas Carlyle and Herbert Spencer on the role of man in history.

Carlyle: the hero, the great individual, the mystical synthesis of a spiritual communion, leads the destinies of humanity towards an unknown, evanescent goal in the chimerical land of perfection and saintliness.

Spencer: nature, evolution, mechanical and inanimate abstraction. Man: atom of a natural organism, one which obeys a law that is abstract as such, but which becomes historically concrete in individuals: immediate utility.

Marx plants himself squarely in history with the solid bearing of a giant. He is neither a mystic nor a positivist metaphysician. He is a historian, he is an interpreter of the documents of the past, of all the documents, not just a part of them.

This was the intrinsic defect of histories, of research into human events: to have examined and taken into account only a part of the documents. And this part was selected not by the historical will but by partisan prejudice, even if it was unconscious and in good faith. What this research aimed at was not truth, precision, the integral recreation of the life of the past, but the highlighting of a particular activity, the bearing out of a prior hypothesis. History was a domain solely of ideas. Man was considered as spirit, as pure consciousness. Two erroneous consequences derived from this conception: the ideas that were borne out were often merely arbitrary, fictitious. The facts that were given importance were anecdotes, not history. If history was written, in the real sense of the word, it was due to the brilliant intuition of single individuals, not to a systematic and conscious scientific activity.

With Marx, history continues to be the domain of ideas, of spirit, of the conscious activity of single or associated individuals. But ideas, spirit, take on substance, lose their arbitrariness, they are no longer fictitious religious or sociological abstractions. Their substance is in the economy, in practical activity, in the systems and relations of production and exchange. History as that which happens is pure practical (economic and moral) activity. An idea becomes real not because it is logically in conformity with pure truth, pure humanity (which exists only as a plan, as a general ethical goal of mankind), but because it finds in economic reality its justification, the instrument with which it can be carried out. In order to know with precision what the historical ends of a country, a 'society, a social grouping are, one must know first of all what systems and relations of production and exchange obtain in that country, that society. Without this knowledge one will be able to write partial monographs, dissertations which are useful for the history of culture, one will pick up secondary reflections, distant consequences, but one will not be doing history, practical activity will not be disclosed in all its solid compactness.

Idols crumble from their altar, divinities see the clouds of perfumed incense disperse. Man acquires an awareness of Objective reality, he masters the secret which lies behind the real unfolding of events. Man knows himself, he knows how much his individual will can be worth, and how it can be made more powerful in that, by obeying, by disciplining itself to necessity, it finally dominates necessity itself, identifying it with its own ends. Who knows himself? Not man in general, but he who undergoes the yoke of necessity. The search for the substance of history, the identification of that substance in the system and the relations of production and exchange, leads one to discover how human society is split into two classes. The class which owns the instruments of production already necessarily knows itself, it has a consciousness, albeit confused and fragmentary, of its power and its mission. It has individual ends and it attains them through its capacity to organize, coldly, objectively, without worrying whether its road is paved with bodies reduced by hunger or corpses on battlefields.

The organizing of real historical causality takes on the value of a revelation for the other class, it becomes an ordering principle for the huge flock without a shepherd. The flock acquires an awareness of itself, of the task which it must now carry out in order to assert itself as a class, becomes conscious that its individual ends will remain purely arbitrary, pure words, empty and inflated wishes, until it possesses the tools until these wishes have become will.

Voluntarism? The word is meaningless, or it is used with the meaning of arbitrary will. Will, in a Marxist sense, means awareness of ends, which in turn means exact knowledge of one's own power and the means to express it in action. It, therefore, means, in the first place, that the class becomes distinct and individuated, compactly organized and disciplined to its own specific ends, without wavering or being deflected. It means an impulse acting in a straight line towards the maximum destination, without jaunts into the green meadows on the wayside to drink a glass of cordial fraternity, softened by the greenery and by tender declarations of respect and love.

But the phrase 'in a Marxist sense' is pointless; it can give rise to equivocations and fatuous showerings of words. Marxist, in a Marxist sense ... the terms are worn like coins that have passed through too many hands.

Karl Marx is for us a master of spiritual and moral life, not a shepherd wielding a crook. He is the stimulator of mental laziness, the arouser of good energies which slumber and which must wake up for the good fight. He is an example of intense and tenacious work to attain the clear honesty of ideas, the solid culture necessary in order not to talk in a void, about abstractions. He is a monolithic bloc of knowing and thinking humanity, who does not look at his tongue in order to speak, who does not put his hand on his heart in order to feel, but who constructs iron syllogisms which encircle reality in its essence and dominate it, which penetrate people's minds, which bring the sedimentations of prejudice and fixed ideas crumbling down and strengthen the moral character.

Karl Marx is not, for us, the infant whimpering in the cradle or the bearded man who frightens priests. He is none of the anecdotal episodes of his biography, no brilliant or gauche gesture of his outward human animality. He is a broad and serene thinking brain, he is an individual moment in the anxious search that humanity has been conducting for centuries to acquire consciousness of its being and its becoming, to grasp the mysterious rhythm of history and disperse the mystery, to be stronger in its thinking and to act better. He is a necessary and integral part of our spirit, which would not be what it is if he had not lived, had not thought, had not sent sparks of light flying from the collision with his passions and his ideas, his sufferings and his ideals.

In glorifying Karl Marx on the centenary of his birth, the international proletariat is glorifying itself, its conscious strength, the dynamism of its aggressiveness of conquest which undermines the rule of privilege and prepares for the final struggle which will crown all its efforts and all its sacrifices.

Signed Antonio Gramsci, II Grido del Popolo, 4 May 1918.* Text taken from An Antonio Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings, 1916-1935, edited by David Forgacs, pp. 36-39.

No comments:

Post a Comment